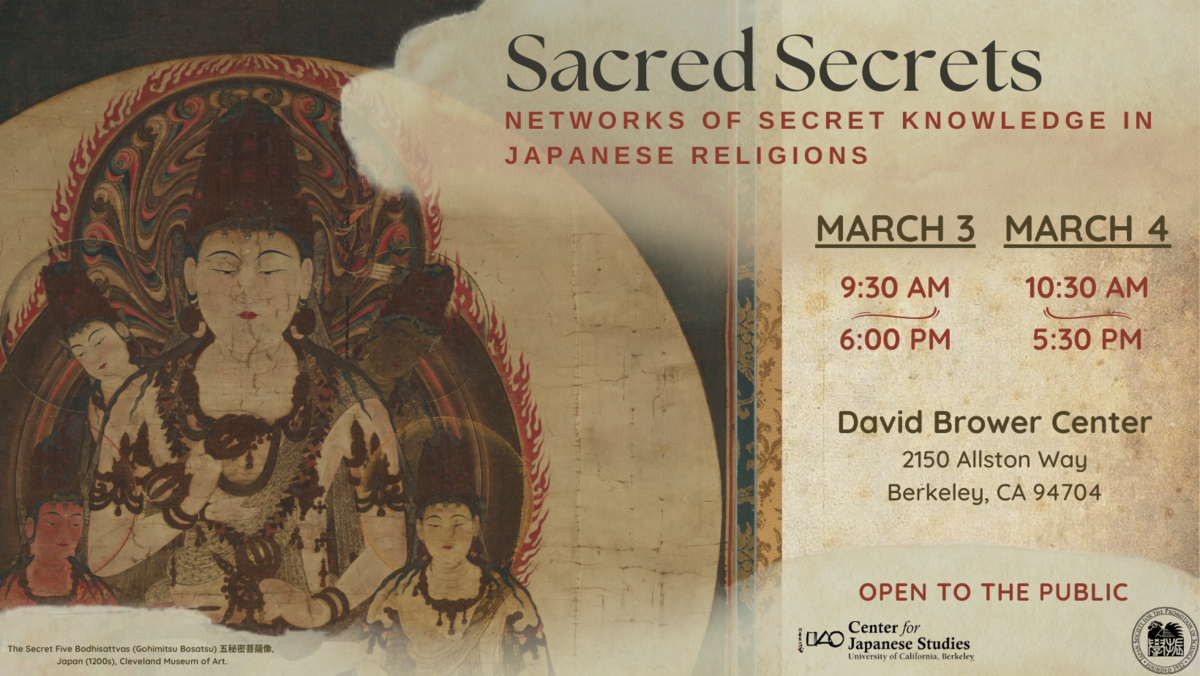

Friday-Saturday, March 3-4, 2023

David Brower Center, 2150 Allston Way, Berkeley, CA 94704

For more than four centuries, the history of Japanese religions has been dominated by secrecy. Secret texts circulated in every group regardless of their affiliation or social status, showing the porosity and pervasiveness of secrecy. Why and how did secrecy become such a central component of religious life? Although works on secrecy abound in the field of European and Tantra studies, the enormous body of Japanese secret works – many of which are recently discovered – has received relatively little attention, casting a shadow on a fundamental aspect of medieval and early modern Japanese religions.

This symposium brings together scholars working on a wide range of topics in the context of Japanese religions to discuss secrecy from different perspectives and methodologies. The aim of this event is to draw attention to the role of secrecy and better illuminate the dynamics underlying the process of “secretization,” the mobility of secrecy, as well as the factors that marked the decline of the culture of secrecy. More broadly, the scope of this symposium is to foster a conversation on Japanese religions from a cross-disciplinary perspective to understand the networks and logics that participated in the creation of religious identities during the Japanese age of secrecy.

Please note: This is a hybrid event. If you'd like to participate in the symposium via Zoom, please register here.

SCHEDULE

Day 1 – Friday, March 3

9:30-09:35 | Opening Remarks by JSPS Director (San Francisco Office)

9:35-09:40 | Opening Remarks by CJS Chair (Junko Habu, Professor, Dept. of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley)

9:40-09:45 | Introduction by the Organizer (Marta Sanvido, Postdoctoral Fellow CJS)

9:50-11:00 | Session 1 - Secret Pure Land

Secrets, Secrecy, Secrecies: Non-Human and Social Concealment in a Shin Buddhist Ritual

Clark Van Doren Chilson, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh

Hiding the Nenbutsu

Mark L. Blum, Professor and Shinjo Ito Distinguished Chair in Japanese Studies, University of California, Berkeley

Chair: Robert H. Sharf, D. H. Chen Distinguished Professor of Buddhist Studies, University of California, Berkeley

11:15-12:25 | Session 2 - Secret Zen

Dōgen’s Quest for the Arcane Import of Zen

William M. Bodiford Professor, University of California, Los Angeles

Revealing the New Aspects of Esoteric Buddhism: From the Activities of Eisai

YONEDA Mariko 米田真理子, Professor, Tottori University

Chair: Marta Sanvido, Shinjo Ito Postdoctoral Fellow in Japanese Buddhism, University of California, Berkeley

1:40-2:50 | Session 3 - Secret Bodies

Esoteric monks and production of secret knowledge on childbirth and women’s reproductive health in medieval Japan

Anna Andreeva, Research Professor of Japanese Language and Culture (Ghent University, Belgium)

Secret Teachings of Waka Poetry and Meditation Practices of Esoteric Buddhism

UNNO Keisuke 海野圭介, Professor, National Institute of Japanese Literature

Chair: Marta Sanvido, Shinjo Ito Postdoctoral Fellow in Japanese Buddhism, University of California, Berkeley

3:00-4:10 | Session 4 - Secret Places

Secrecy, Hagiography, and Place

Marta Sanvido, Shinjo Ito Postdoctoral Fellow in Japanese Buddhism, University of California, Berkeley

Territories of Secret Transmission in Medieval Japan: Shōtoku Taishi Legends as a Frame of Reference

ABE Yasurō 阿部泰郎, Professor, Ryūkoku University

Chair: Mark L. Blum, Professor and Shinjo Ito Distinguished Chair in Japanese Studies, University of California, Berkeley

4:30-6:00 | Keynote Address

The Language of Secrecy: Allegoresis in Medieval Japanese Culture

Susan Blakeley Klein, Professor of Japanese Literature and Culture, Director of Religious Studies, UC Irvine

Day 2 – Saturday, March 4

10:30-12:15 | Session 5 - Secret Rituals

New Findings in the Kokūzō Bosatsu Gumonji-hō in Medieval Japan

KIKUCHI Hiroki 菊地 大樹, Professor, Historiographical Institute — The University Tōkyō

The History of the Kurodani Lineage of Tendai’s Consecrated Ordination (Kai Kanjō 戒潅頂): Ritually Embodying "The Lotus Sutra"

Paul Groner, Professor Emeritus, University of Virginia

Secret Teachings of Miwa Shōnin Kyōen and Estoteric Shintō

ITŌ Satoshi 伊藤聡, Professor, Ibaraki University

Chair: Mark Blum, Professor and Shinjo Ito Distinguished Chair in Japanese Studies, University of California, Berkeley

1:30-2:40 | Session 6 - Secret Vows

Devotional Disclosures: On Prayer Texts and Mandalas

Heather Blair, Professor, Indiana University Bloomington

Sex, Lies, and Kishōmon or Japanese Religious Oaths: the Public, the Private, and the Secret

D. Max Moerman, Professor, Barnard College

Chair: Robert H. Sharf, D. H. Chen Distinguished Professor of Buddhist Studies, University of California, Berkeley

2:50-4:20 | Session 7 - Secret Music

Secrecy in the Transmission of Buddhist Chant

Michaela Mross, Assistant Professor, Stanford University

Performance and Performativity: Religious Aspects of the Secret Repertory of Gagaku Musicians (presentation followed by a music performance)

Fabio Rambelli, Professor, University of California, Santa Barbara

Chair: TBA

4:30-5:00 | General Discussion

5:00 | Closing Remarks

ABSTRACTS

Day 1 – Friday, March 3

Session 1 - Secret Pure Land

Secrets, Secrecy, Secrecies: Non-Human and Social Concealment in a Shin Buddhist Ritual

Clark Van Doren Chilson, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh

J. Z. Smith in his essay “Religion, Religions, Religious” shows how the taxonomy of “religion” changed over time and how the term can be defined in many ways. In this essay, which is less historical than conceptual in orientation, I argue we can understand secrecy in Japanese religious contexts better and can do more sophisticated and precise comparative studies if we identify multiple modes of concealment. Based on an analysis of the core soteriological ritual called ichinen kimyō in a modern covert Shin Buddhist tradition, this paper delineates three types of secrecy: mystery in which the concealer is non-human; esotericism, which involves both non-human and human concealment; and social secrecy which involves people concealing from other people. It shows how there are different forms of secrecy (i.e., secrecies) that are distinguishable but not mutually exclusive. It further reveals the relationship among secrecies in a particular ritual that allows us to more fully appreciate the complexities of concealment and keeps us from making fallacious or simplistic claims about what secrecy is and does.

Hiding the Nenbutsu

Mark L. Blum, Professor and Shinjo Ito Distinguished Chair in Japanese Studies, University of California, Berkeley

Nenbutsu practice associated with Pure Land Buddhism in Japan has an esoteric, secret dimension to it within the esoteric traditions of the Shingon and Tendai sects from the late-Heian period that is to be expected. But when nenbutsu achieved a special authority within the new Pure Land schools established in the Kamakura period, the rhetoric supporting nenbutsu as uniquely efficacious emphasized its universal access and ease of practice, both reflecting the need for openness recognized by Śākyamuni and Amida. There are three explicit ways, however, in which the traditions of Hōnen and Shinran developed dimensions of secrecy after the deaths of their founders that I will discuss. First is an apocryphal esoteric text attributed to Hōnen, Ketsujō ōjo himitsugi. The other two are associated with Shinran’s Jodoshin sect: the kakure-nenbutsu that started in Satsuma province in the early 16th century and continued until at least the Meiji period, and the kakushi-nenbutsu movement based in the Tōhoku region, traced to the Edo period. Hōnen’s text, supposedly written on Mt. Hiei before his “conversion”, reflects taimitsu tradition in identifying original enlightenment with Amida. Kakure-nenbutsu was akin to kakure-kirishitan in preserving nenbutsu culture in spite of Satsuma provincial leaders banning the Shin sect starting around 1500, intimidating believers with physical punishment and rewards for conversion. In Tōhoku, innovative changes to nenbutsu practice resulted from a fusion of Shingon traditions associated with Kakuban and affirmed by priests from the Bukkōji branch of Shin, at times associated with Shinran’s disgraced son, Zenran. In Iwate, Sendai, etc., secret transmissions of rituals, initiations, images, were extensive, some hidden from officials to avoid corporal punishment. Why was there a need to ascribe a Tendai esoteric text to Hōnen? Why did these Shinshu innovations need to be secret—what threat did they pose politically and did their secrecy increase their value?

Session 2 - Secret Zen

Dōgen’s Quest for the Arcane Import of Zen

William M. Bodiford Professor, University of California, Los Angeles

Secrecy as ideology and as ritual practice constitutes an essential feature of social life. It

functions in ways beneficial or sinister depending on individual perspectives. And, not

infrequently, both aspects appear simultaneously within a shared perspective or framework.

Descriptions of the culture of secrecy within Sōtō Zen typically characterize secret initiations as

problematic legacies of the medieval dark ages when the actual teachings of Dōgen (the titular

founder of the Sōtō lineage in Japan) had become inaccessible and were largely supplanted by

popular religious practices derived from other sources. Nonetheless, the tradition celebrates a key episode in the religious biography of Dōgen when he quested for the arcane import of Zen. Dōgen’s achievement of this quest, first and foremost, confirmed his legitimacy as the first patriarch of Sōtō Zen in Japan. It likewise legitimated the rituals of secret initiations that

developed in subsequent generations after Dōgen’s death.

Revealing the New Aspects of Esoteric Buddhism: From the Activities of Eisai

YONEDA Mariko 米田真理子, Professor, Tottori University

Eisai’s educational activities have been discussed in accepted theory centering on Zen beliefs, that is, the new Song dynasty Chan. This study reconsiders the true picture of Eisai and clarifies that at his core was a belief in esoteric Buddhism. How did Eisai understand the relationship between existing esoteric Buddhism and Zen? In order to elucidate this, I reconsider the characteristics of Eisai’s esoteric beliefs and bring to light new aspects of esoteric Buddhism in early medieval times.

Session 3 - Secret Bodies

Esoteric monks and production of secret knowledge on childbirth and women’s reproductive health in medieval Japan

Anna Andreeva, Research Professor of Japanese Language and Culture (Ghent University, Belgium)

Buddhist expertise on childbirth and women’s health emerged at esoteric temples in the late ninth century. Although the earliest rituals for safe childbirth may have been conducted for an imperial consort by Kūkai’s brother and disciple, the Shingon monk Shinga 真雅 (801–879), the first handbook on childbirth and women’s reproductive health was attributed to the Tendai scholar-monk Annen 安然 (840?–880?). The compilation of this short handbook, composed of quotations from Indian and Chinese esoteric sutras and philosophical treatises, is thought to be related to the 850s imperial succession crisis and subsequent rise of the Fujiwara regents, when women from the elite layers of the Fujiwara clan came to be increasingly accepted as imperial consorts. Since then, the secret knowledge on ritual and medico-religious methods to enhance or preserve women’s reproductive health had acquired special currency among Tendai and Shingon clerics and their elite clients.

This paper will trace the production and circulation of such expert knowledge within esoteric temple networks in early and medieval Japan, during the ninth- to fourteenth centuries. Starting with Annen’s handbook titled Gushi nintai sanshō himitsu hōshū 求子妊胎産生秘密法集 (Collection of Secret Methods on Conception, Pregnancy and Childbirth), this paper will analyse the uneven itinerary of secret knowledge on women’s health, affected by competition between different esoteric lineages and elite clerics. Then, touching upon the issue of secret rituals, aimed to protect pregnant imperial consorts and their unborn children, this paper will try to explain how Annen’s handbook was re-used by the Shingon esoteric networks in medieval Japan to compose an even grander two-fascicle manuscript titled Sanshō ruijūshō (Encyclopaedia of Childbirth), which may have been produced at Daigoji in the late thirteenth century, and copied at the temple Shōmyōji near Kamakura in 1318.

Secret Teachings of Waka Poetry and Meditation Practices of Esoteric Buddhism

UNNO Keisuke 海野圭介, Professor, National Institute of Japanese Literature

From quite early on waka was a self-defining genre that queried “What is it about?” In this regard, the preface to Kokin Wakashū written in 905, reads “the seeds of Japanese poetry lie in the human mind and grow into leaves of ten thousand words.” This contraposition of minds and words presented in an extremely short phrase defines the relationship between the “words” that expressed the “minds” of people which is the main subject in waka poetry composition. This became the basic framework for thinking about the essential characteristics of waka, and it has been discussed in various ways for over one thousand years.

A major culmination of the development of these discussions took place from the latter Heian period to the Kamakura period. In relating “minds” with “words,” the late Heian period poet Fujiwara no Toshinari (1114–1204) quoted from the Mohe Zhiguan by the Tiantai Patriarch Zhiyi (538–597), considered a cardinal scripture in the Tendai tradition to explain its theory. While Toshinari’s son Fujiwara no Teika (1162–1241) and his grandson Fujiwara no Tameie (1198–1275) did not bring religious theory into discussions of waka, the poet and Tendai prelate Jien (1155–1225), who was active at the same time as Teika, has left in his writings the concept of uniformity between waka and Shingon Darani. Moreover, Tameie’s illegitimate son Tameaki (1242–?), and those in the same school, explained the significance of waka by quoting the major writings and iconography dependent on sermons of the Shingon school that described the relationship between the physical body and human consciousness.

Reflecting on the course of poetry theory from the twelfth to thirteenth centuries, we can comprehend the shape of the discussion concerning human “minds” in the history of waka as developing by utilizing complex Buddhist concepts and Buddhism's methods of interpretation. The writings left by Toshinari and Jien have been examined by many in the past. However, the foundation of Buddhist theory on which the discourse by Tameaki and those around him stands is not always clear, necessitating the excavation and examination of Buddhist materials in order to ascertain their content to add to the discourse.

In recent years advances have been made in the survey and examination of materials held by Shingon sect temples, with several materials discovered allowing for specific studies of the discourse surrounding Tameaki. This paper offers an examination of the materials related to the discourse on “minds” from the religious side with materials from Gogakusan Zentsūji (Zentsūji City, Kagawa Prefecture) holdings of writings on controlling the breath as meditation methodology, titled Himitsu Susokukan, said to be written by the Kamakura period Shingon priest Dōhan (1178–1252), and the Ajikan method of contemplation in materials of an unknown writer in the collection of Amanosan Kongōji (Kawachi Nagano City, Osaka Prefecture). Along with discussing their influence on the discourse concerning “minds” and “words” in the history of waka, I will also cover the development of the discussion of the methods of contemplation contained in these materials.

Session 4 - Secret Places

Secrecy, Hagiography, and Place

Marta Sanvido, Shinjo Ito Postdoctoral Fellow in Japanese Buddhism, University of California, Berkeley

This presentation investigates the evolution of the hagiography of the First Chan Patriarch, Bodhidharma, in Japan and its connection to a set of secret rituals.

The story goes that Bodhidharma was reborn as a pauper on the grounds of Mt. Kataoka, on the outskirts of Nara, where he met the Crown Prince Shōtoku Taishi (574–622). Eventually, Bodhidharma disappeared without leaving any traces, yet the significance of the event and the karmic connections that it inspired were disputed for more than eight centuries among Buddhist clerics. Scholars have directed their attention to the figure of Shōtoku and the overall implications of the parable for the Prince’s cult. However, following the establishment of Zen schools during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), this story became part of the official hagiography of Bodhidharma and originated an intricate web of textual and multi-media hagiographic products.

Among these, a set of Sōtō Zen secret documents known as kirigami (paper strips) used the tale to explain a ritual technique ascribed to Bodhidharma and employed to predict the moment of death.

By tracing the genealogy of this ritual and its connection with Bodhidharma’s hagiography, this paper problematizes two aspects concerning secret insights, 1) the interdependence of covert and overt networks and notions; 2) the multi-genre and multi-form nature of secrecy, which requires a reconsideration of commonly adopted categorizations, such as literary/religious, doctrinal/ritual, secret/public.

Territories of Secret Transmission in Medieval Japan: Shōtoku Taishi Legends as a Frame of Reference

ABE Yasurō 阿部泰郎, Professor, Ryūkoku University

A major field that characterizes the world of religious texts in medieval Japan is the aspect of what is called “secret oral instruction.” Who created these texts, what sort of influence did they have on the medieval world, and what was the outcome? A suitable survey of these issues can be viewed by examining the culture of medieval belief in Shōtoku Taishi (574–622), or briefly, the religious texts known as Shōtoku Taishi legends.

As shown in the Nihon Shoki, the tales about Shōtoku, which were created as an inseparable part of the formation of ancient images of the nation, mythologized the role of Shōtoku Taishi in the flourishing of Buddhism. The many teachings of Shōtoku and the origins of the various temples said to have been founded by the Prince were consolidated, resulting in the creation of Shōtoku Taishi Denryaku, at the end of the tenth century. While the annotations to the Denryaku led to its canonization, during the transition from ancient to medieval times, at the historical sites connected to Shōtoku, not only were new religious texts about the Prince created, but also these temples were turned into sacred places. Examples include the origin of Shitennōji with its own Goshuin Engi, the relics inside Shōtoku Taishi’s hands becoming part of the Prince’s treasure at Hōryūji, and new manifestations of Taishi, such as Kōtoku Taishi (Shōtoku offering filial piety) and Namubutsu Taishi (Mantra chanting Shōtoku). In short, in conjunction with the emergence of a new network of scriptures about Shōtoku, the temples founded by the Prince turned into sacred places.

In this process, at temples such as Shitennōji, Hōryūji, and Tachibanadera, along with the authority from the annotated Denryaku, the phenomenon of the mystification of teachings appeared in conjunction with turning the annotations into religious texts. The typical form of this is Hōryūji’s posthumous Shōtoku Taishiden Shiki, the result of the joint effort of ideologues such as Jokei, Keisei, and Eison who guided, revived, and solicited contributions to medieval Buddhism. The ripple effect of this secret teaching developed further into the creation of new traditions of Shōtoku and his culture.

Shōtoku’s illustrated biography at the Picture Hall (Kaidō) at Shitennōji is how Shōtoku legends were given visual form in medieval Japan. The fourteenth-century preaching text entitled Shōbōrinzō, by relying on the aforementioned Prince’s illustrated biography, incorporated the secrets that proliferated in the annotations of the Denryaku to craft an entirely new image of Shōtoku.

This paper will introduce some of these examples to illuminate the multiple aspects of medieval Japanese culture—from the scholarly to the artistic domains—forming the “systems of knowledge” that generate secrecy. By using Shōtoku legends as one such path, we can trace the itinerary that led to the creation and dissemination of secrecy, ultimately culminating in the mythology surrounding imperial authority.

Keynote Address

The Language of Secrecy: Allegoresis in Medieval Japanese Culture

Susan Blakeley Klein, Professor of Japanese Literature and Culture, Director of Religious Studies, UC Irvine

To understand the culture of secrecy in medieval Japanese culture, it is important to

understand what might be called the “episteme” of the medieval Japanese, that is, their attitude towards the signifying power of signs. What do words mean? What do images mean? How are we to read them properly? Since the early 20 th century, beginning with Ferdinand de Sausure, when linguists have discussed the problem of signification, they have talked about the signifier (the sign as word or image) and the signified (what that word or image represents in the “real” world). A grounding assumption of Saussurean linguistics was that the relationship between the signifier and signified is arbitrary; for example, there is a real-world referent “dog” which has widely varying linguistic signifiers (dog, inu, chien, pero) depending on the language. There is nothing in the signified that dictates the word representing it has to be any particular word – the relationship is considered arbitrary.

What is striking about the medieval Japanese attitude towards the signifier/signified

relationship is that it is not considered arbitrary, but instead is seen as motivated (and ultimately non-dual). This meant that the surface “meaning” of practically any linguistic or material signifier (Sino-Japanese characters, poetry, icons, clothing/costumes, sacred spaces, etc.) could be analyzed productively to show profound truths about phenomenal (and even absolute) reality, particularly hidden identities. And one of the main methodologies used to reveal these hidden identities was etymological and numerological allegoresis: reading metaphorical associations, punning identifications, paronomasia (the analysis of Sino-Japanese characters into their component parts), and numerological homologies into and onto linguistic or material signifiers so as to provide insight into a hidden reality. This allegorical reading strategy, which could be considered the practical application of the medieval epistemic understanding of the symbolic relationship, is ubiquitous in medieval Japanese religious texts, particularly those encountered atthe conceptual intersection of Esoteric Buddhism and kami worship. On a popular level, this understanding of the symbolic relation enabled the medieval ideology of honji suijaku, in which kami and Buddhist deities were enmeshed in a complex pattern of associational identification. We can see a more elite version of this episteme at work in medieval Shingon Buddhism’s multi-leveled pedagogical system, in which initiates were introduced to progressively more sophisticated levels of semiosis. In the secret texts and commentaries related to artistic production, on the other hand, the level of semiotic sophistication varies quite a bit from text to text, depending on authorship and audience. It is clear, however, that for all of these texts, both religious and artistic, the notion of the ultimate non-duality of signifier and signified transformed the material world into a virtually unlimited field of semiotic play.

Day 2 – Saturday, March 4

Session 5 - Secret Rituals

New Findings in the Kokūzō Bosatsu Gumonji-hō in Medieval Japan

KIKUCHI Hiroki 菊地 大樹, Professor, Historiographical Institute — The University Tōkyō

The transmission of the Gumonji-hō (ritual to strengthen the memory), which has as its principal image Kokūzō Bosatsu (bodhisattva Ākāśagarbha), traces back to the stages of early esoteric Buddhism, with a close relationship to ancient ascetic practices in mountain forests. Gumonji-hō was an ascetic practice often performed in medieval and early modern Japan, with many ritual rules and notes on oral instruction that remain. It was considered that there were no major changes in its contents after medieval times and became embedded in the various ritual services involving different deities. However, the Gumonji-hō underwent a fundamental transformation in the twelfth to thirteenth centuries by incorporating the latest esoteric Buddhist teachings from the Taimitsu Tani-ryū school such as the merging of the principle and wisdom, and the three points of principle, wisdom, and matter of the Tōmitsu Daigo Sanryū, and others. In that process Kakuban (1095–1143), Eisai (1141-1215), Enni (1202–1280), Nichiren (1222–1282), and others were involved. While basing my findings on documents on oral transmission and learning concerning the Gumonji-hō in medieval Japan, this paper will inquire into the influence they had on Buddhism overall in the Kamakura period.

The History of the Kurodani Lineage of Tendai’s Consecrated Ordination (Kai Kanjō 戒潅頂): Ritually Embodying "The Lotus Sutra"

Paul Groner, Professor Emeritus, University of Virginia

The consecrated ordination is a highly elaborated ordination ceremony. Although the use of the term kanjō (Skt. abhiṣeka) suggests Esoteric Buddhist associations, kanjō were also used in the coronation of kings when waters from various rivers might be combined and poured over the new king’s head to represent his domination over an area. In Buddhism, the stage of a bodhisattva about to become a Buddha was sometimes characterized using this term.

The consecrated ordination was characterized by secrecy so that a teacher and his disciple were said to embody the Lotus Sutra scenario when Śākyamuni climbed into Prabhūtaratna’s pagoda and sat next to him. This re-enactment of a famous scene was frequently said to not be Esoteric but rather a Lotus Sutra ceremony. Analyzing this ceremony, which is still performed today, involves a consideration of the differences between secrecy in Esoteric Buddhism and in Tendai original enlightenment (hongaku 本覚) thought. In this paper, I examine a number of documents published for the first time during the last few decades in the Zoku Tendaishū zensho to trace some of these developments. The paper thus updates research done for my recently published book Precepts, Ordinations, and Practice in Medieval Japanese Tendai.

In this paper, I look at a variety of recently published Korodani commentaries and ritual manuals, some of them apocryphal texts attributed to major Tendai figures, to trace developments that led to the consecrated ordination.

Secret Teachings of Miwa Shōnin Kyōen and Estoteric Shintō

ITŌ Satoshi 伊藤聡, Professor, Ibaraki University

Kyōen (1140–1223), who was called Miwa Shōnin, was a priest who lived in the Miwa bessho, and wandered to various locations as a practicing ascetic. He was also known as a mountain practitioner with special powers to converse with the gods and tengu.

The mystical treatment of him continued after his death, and he was considered the founder of the Miwa-ryū and became venerated as the creator of the Miwa Shintō, one of the Shintō schools. In this process, various secret teachings and secret stories were created. They include the verses about enlightenment within this very body received from the Dragon Princess on Mt. Murō; the Ise abhiṣeka attained in the form of a snake by Amaterasu; the secret teachings inherited from living Jizō; and the mutual initiation of esoteric teachings with the Deity of Miwa. This study examines the many secret teachings of Kyōen and reflects on the form of medieval esoteric Shintō

Session 6 - Secret Vows

Devotional Disclosures: On Prayer Texts and Mandalas

Heather Blair, Professor, Indiana University Bloomington

Drawing on literary prayer texts (ganmon) composed during the late Heian period, this project treats mandalas not as supports for esoteric ritual, nor as works of art, nor yet as “secrets of mind” that instantiate the enlightened and enlightening reality of the dharmakāya and dharmadhātu. Instead, it frames mandalas as objects produced and then dedicated by laypeople in exoteric offering rites aimed at securing such benefits as longevity and beneficial rebirth for themselves and their loved ones. Focusing on prayer texts written for lay patrons by the noted man of letters Ōe no Masafusa (1041–1111), this paper shows that laypeople regularly commissioned mandalas of different types, which they combined with a broad range of other offerings and practices—the dedication of sculptural icons, sutra copying, repentance, mourning, and more. Whereas to date the theoretical and ritual practices of educated male monastics have dominated research, this project shifts our attention toward questions of how mandalas circulated and transformed within the broader context of ecumenical lay religious practice.

Sex, Lies, and Kishōmon or Japanese Religious Oaths: the Public, the Private, and the Secret

D. Max Moerman, Professor, Barnard College

Divine punishment oaths (tenbatsu kishōmon 天罰起請文), performed orally before the altars of the buddhas and kami, and inscribed on temple and shrine talismans (goōhōin 牛王宝印), were among the least secret of Japanese religious practices. They were purposely public acts which entailed an audience to witness the performance, a recipient to accept the vow, a punishment visible to all, and often a juridical body to evaluate and render judgement. Swearing an oath before the gods was an overt social act instrumental to forming and maintaining the public institutional structures of Japan society from the thirteenth to the nineteenth century. They were sworn by farmers to complain of mistreatment by authorities and to justify rebellions; by merchants to forestall and defend themselves from accusations of theft and mismanagement, by magistrates and litigants to adjudicate claims and authenticate affidavits; by warriors to pledge allegiance and guarantee fealty; and by military governments in oaths of office and codes of law. Divine punishment oaths constituted the media and the mechanism by which social bonds were established and by which the economic, legal, and political order was secured. Within the history of such an overt and public religious practice, however, there is one type of divine punishment oath inscribed on temple and shrine talismans that remained secret: oaths of romantic and sexual devotion. This paper will examine love oaths produced by a thirteenth-century imperial abbot, a sixteenth-century daimyo, and the denizens of the urban pleasure quarters of the seventeenth and eighteenth century, among others, to ask what such intimately private examples an otherwise explicitly public religious practice might reveal about the culture of secrecy in Japanese religions.

Session 7 - Secret Music

Secrecy in the Transmission of Buddhist Chant

Michaela Mross, Assistant Professor, Stanford University

The vocalization of sacred texts has long played a vital role in Japanese Buddhism. Clerics of all Buddhist schools vocalize sutras and other sacred texts during the daily services, often accompanied by percussion instruments such as the wooden fish (mokugyo 木魚). On special occasions, clerics perform highly musical rituals during which they sing liturgical texts with elaborate melodies in free rhythm that belong to the repertoire of traditional Japanese Buddhist chant (shōmyō 声明). Moreover, lay devotees regularly recite shorter sutras, such as the Heart Sutra, or Buddhist hymns in Japanese, including goeika 御詠歌 (devotional songs) and wasan 和讃 (Japanese hymns).

This paper studies secrecy in the transmission of Buddhist chant. Shōmyō is vocalized exclusively by Japanese clerics and transmitted from master to disciple. Shingon and Tendai clerics further consider certain chants, such as Nyoraibai 如来唄 (Praise of the Thus Come One), as secret pieces, only taught to disciples who have mastered the basic liturgical chants. Lay devotees are generally excluded from receiving instruction in shōmyō. However, in the 1920s and 30s, Shingon monks established new goeika lineages, in which both clerics and lay devotees sang Buddhist hymns together. Sogabe Shunnō 曽我部俊雄 (1873-1959), one of the founders of the goeika lineage of Kōyasan, suggested that goeika chanting is shōmyō for lay devotees, aiming to expand the practitioner base of Buddhist chanting. Nonetheless, the teachers of the new goeika lineages taught only members of the choirs affiliated with their lineages; thus they kept a certain degree of exclusivity. In this paper, I will illuminate the different levels of secrecy that characterizes Japanese Buddhist chant.

Performance and Performativity: Religious Aspects of the Secret Repertory of Gagaku Musicians (presentation followed by a music performance)

Fabio Rambelli, Professor, University of California, Santa Barbara

Various forms of secrecy played an important role in premodern Japanese religion, as they were related to the control and transmission of knowledge, the status and efficacy of rituals, and aspects of legitimization and prestige. Many procedures for the control and preservation of secrecy were modeled upon an Esoteric Buddhist initiation/consecration ceremony, kanjō (Skt. abhiṣeka), which was used initially for both the enthronement of kings/emperors and the consecration of monks. It was later modified and adapted to fit different contexts, both within Buddhist institutions and outside of them in "secular" practices, such as professional activities and, most prominently, the arts. Some have seen the adoption of variants of kanjō rituals within the performing arts as an indication of a process of de-sacralization of an originally religious ritual away from Buddhist institutions; while this may be true in some instances, it was not always and necessarily the case.

This paper explores multiple ways in which professional Gagaku musicians (gakunin) from the traditional lineages responsible for the transmission of instrumental music (kangen), songs (utaimono), and dances (bugaku) at the imperial court and at the leading temple-shrines complexes, extensively adopted secret procedures for multiple purposes, including the performance of religious or quasi-religious rituals or the achievement of religious or quasi-religious goals, such as propitiation of divinities or the purification from the influence of evil spirits.

In this paper, I begin with an outline of the degrees of secrecy involved in learning and transmitting the Gagaku/Bugaku repertory, and then focus on the most secret types of knowledge and performing practices in the middle ages and the early modern period, that is, those concerning the so-called "secret compositions" (hikyoku) and the most prestigious Bugaku dances, respectively. I will then discuss 2-3 little-known cases in which gakunin were directly involved in secret ceremonies, such as the mikagura performances at court and other elusive rites involving music (at court, at temples, and among the samurai).

Finally, by way of conclusion, I will question the applicability of our established categories of religious/secular, or sacred/profane, pointing to their inadequacy when discussing activities in which a performance is considered performative, that is, the instantiation of transformations affecting performers, participants, and metahuman beings also involved.